Summary

Absorption turned negative in consecutive quarters for only the second time in the last 11 years, rent growth continues to decelerate, and quarterly investment volume is about 60% lower than at this point last year. With nearly 4 million SF in the supply pipeline and lingering uncertainty regarding the economy, the Miami office market will likely face several quarters of rising vacancy rates, continuing the weakening seen since midyear 2020.

Firms are reevaluating future space needs considering health protocols necessitated by the pandemic and a successful large-scale work-from-home experiment. To gain clarity on these fronts, even many financially stable office occupiers are either delaying space decisions or opting for short-term renewal leases.

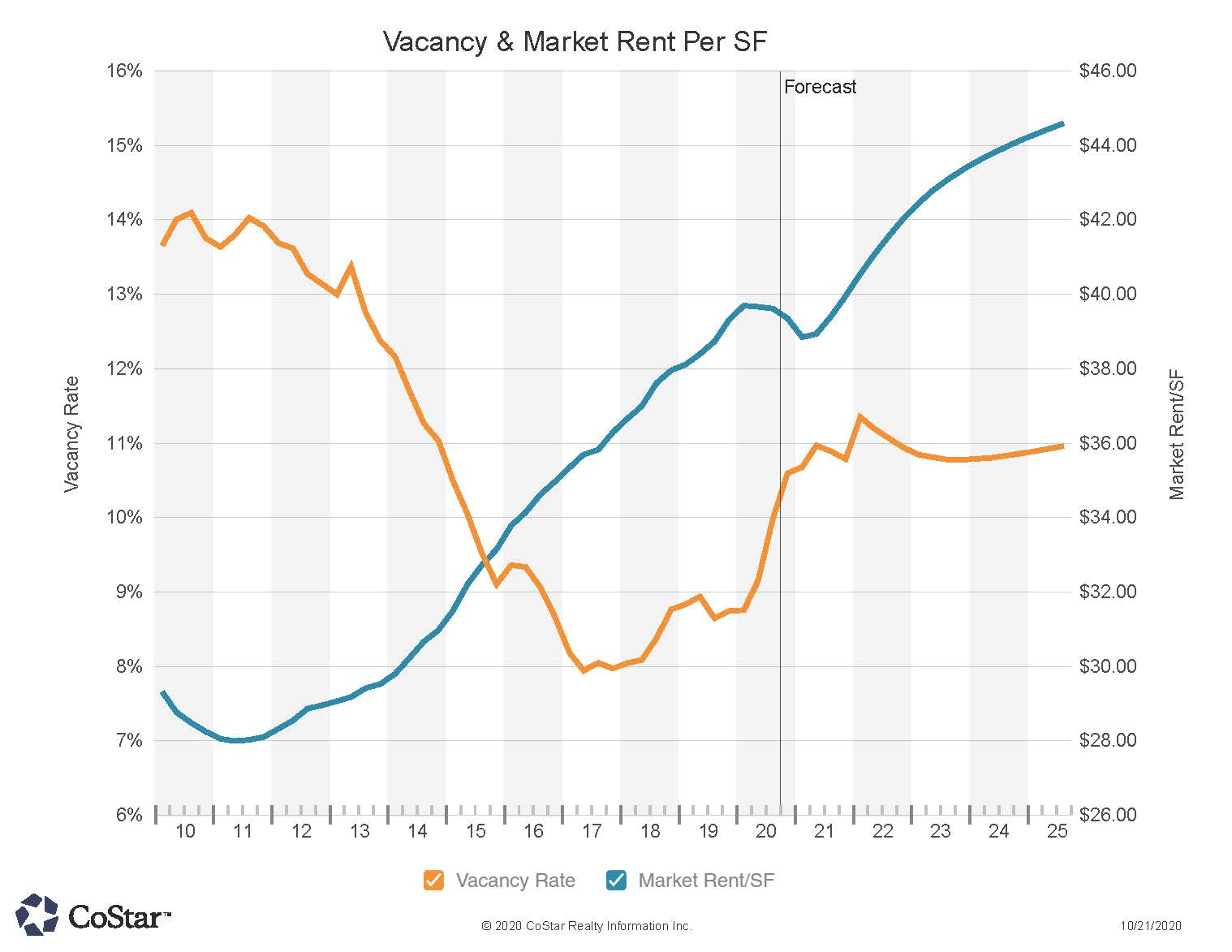

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic taking hold, Miami’s office market was on solid footing, with the vacancy rate sitting about 150 basis points lower than the historical average. Rent growth continues to outperform the national average, though the pace of growth has rapidly decelerated.

Flexible office providers of both local and national brands were on a leasing binge the past several years. But given the facts that the much of the country is limiting human interaction and most office workers continue to work from home, near-term demand for co-working and flexible office product will remain measured. WeWork closed its 40,000-SF location at 350 Lincoln Road in Miami Beach, citing cost savings and the presence of another location in Miami Beach. The closure comes on the heels of the building’s landlord filing a lawsuit alleging nearly $20 million in unpaid rent.

Current office construction levels in the Miami metro are the highest seen since mid-2009. More than 1 million SF more is expected to deliver by the end of the year. Projects with minimal preleasing will struggle to secure tenants in the current leasing environment. Looking ahead, new high-quality assets with next-generation ventilation and air filtration systems may see stronger demand as office tenants put a premium on employee safety.

As a coastal market with international appeal, Miami had a strong capital markets environment before the pandemic took hold. The market posted a solid stretch of elevated dollar volume and robust price appreciation. However, investment volume decelerated from the end of 2019 through mid-2020. The third quarter volume total increased, though the figure was skewed. If not for one large portfolio deal which accounted for the majority of the third quarter total, the picture would be far less impressive. Near-term forecasts for pricing call for declines on a per-SF basis as well as cap rate expansion. However, to what extent pricing will be impacted remains uncertain.

Many investors are likely to take a wait-and-see approach for the near term. The inability of investment committees to travel to see an asset, uncertainty in the debt markets regarding underwriting and buyers looking for distressed pricing will likely keep downward pressure on volume totals. Longer term, the debate continues regarding the need for office space in the future. There are arguments for firms needing less space per employee by continuing to adopt work-from-home flexibility, and there are equally compelling arguments for tenants needing more space per employee and additional satellite offices to implement and “hub-and-spoke” model.

Leasing

Prior to the third quarter, the vacancy rate has been in the single digits and hovering well below the market’s long-term average since 2015. Since midyear, net absorption has been decidedly negative. The market has not seen this level of negative demand in consecutive quarters since the Great Financial Crisis in 2009.

Leasing totals declined precipitously from the first quarter. The 400 deals signed at the start of the year was roughly on par with the quarterly average over the last two years. However, the total number of deals signed was 50% lower at midyear. In terms of volume, the drop-off was even more pronounced, with the second quarter totals nearly 60% lower than the two-year average.

Another concern is the rapid increase in the amount of available sublease space. Since mid-2020 about 320,000 SF of additional available sublease space has been added to the market, an increase of 40% in just one quarter. Late in the third quarter there was 1.1 million SF of available sublease space posted on CoStar. Sublease availabilities are particularly elevated in the Miami Airport, Downtown Miami, Brickell and Kendall submarkets. These four submarkets account for 75% of all available sublease space.

Elevated sublease space is a concern for landlords, since it usually offers a discount to tenants, given the inability, typically, of tenants to negotiate lease terms and tenant improvements. This adds competition to the direct space landlords attempting to fill in an economic downturn, often resulting in greater market-wide downward pressure on asking rents.

Sublease space hitting the market may imply some office users are reconsidering their longer-term space requirements. Whether it is from financially unstable firms contracting or healthy firms realizing they need less space if more workers will work from home for the foreseeable future, the rise could portend weakening future space demand.

Leasing activity is expected to remain relatively muted for the near term and vacancy will likely continue its ascent as a significant amount of supply is scheduled to deliver. Office-using firms from a wide range of industries will likely continue to delay leasing decisions for the foreseeable future given the current economic conditions and uncertainty regarding future space needs.

Rent

Annual rent growth in Miami was healthy heading into this downturn, averaging between 3%-5% over the past two years. While still positive, the pace of growth in the third quarter has significantly decelerated from the start of the year as buildings sit mostly empty and landlords have lost some pricing power as tenants consider space needs going forward. CoStar’s forecast calls for rent growth to turn negative by year-end, though remaining above the national average as it largely has since 2015.

While asking rent growth has slowed in the third quarter, wholesale discounts have not yet become prevalent in the metro. Since the beginning of March, CoStar researchers recorded a change to asking rent in about 400 spaces across the Miami metro. Of the spaces with a recorded change, slightly fewer than 50% lowered the asking rent. As such, many of the areas seeing spaces with a decline in asking rent, such as Brickell, Miami Beach and Miami Airport have also seen a comparable number of spaces increase the asking rent.

However, stable asking rents may be masking large concession packages, particularly in high-vacancy submarkets and buildings. Tenants willing to make a large, long-term commitment in this climate likely have some measure of leverage.

Miami’s solid rent gains prior to the pandemic are largely thanks to the performance of the Brickell submarket. Strong demand from a diverse tenant base including major law firms like Holland & Knight LLP and Akerman along with financial institutions such as Bank of America Merrill Lynch, HSBC and Banco Santander has fueled rent gains. These firms generally prefer top-quality space along Brickell Avenue, despite market leading asking rent topping $53/SF. As much of the demand over the last decade has been in 4 and 5-Star properties, Brickell benefits as more than 60% of the submarket’s inventory is in that top-quality segment. Rents can surpass $60/SF in Brickell, as evidenced by law firm Bursor & Fisher’s lease at the 5-Star 701 Brickell Ave. signed in April. The starting rent was $65/SF on a full-service basis with 3% annual escalations.

New supply in Brickell is set to test the upper limits of what tenants are willing to pay as the 4-Star 830 Brickell has an asking rent of $75/SF full service despite being only 30% preleased.

If landlords opt to maintain current face rents in the greater metro, the amount offered to tenants in the form of concessions, particularly tenant improvement allowances and free rent, may increase as a result. However, should sublease space continue to spiral upward as a result of companies either dealing with financial hardship or rethinking their space needs due to the success of remote work policies, landlords with large blocks of direct space will feel even more pressure to lower their asking rents. CoStar’s forecast predicts that declines in asking rents to have only just begun, and that by early 2021 rents in Miami will have fallen by some 3% – about half as steep as the overall national average.

Sales

The economic uncertainty from the coronavirus pandemic had an impact on investment sales as the second quarter volume total was more than 40% lower than the start of the year. The was an uptick as the second half of the year began, however, one large portfolio transaction accounted for the majority of that third quarter volume total.

Over the past year, the makeup of buyer and sellers shows that institutional investors have shifted their attention to other markets, as that group made up only 2% of buyers as opposed to 44% of sellers in terms of sales volume. Conversely, private equity and REITs accounted for less than 1% of volume as sellers, but were buyers for 22% and 14% of volume, respectively.

The average modeled price per SF currently stands at about $330, slightly above the national average of $324. Likewise, average market cap rates are outperforming at 6.1%, compared to the national average of 6.9%. Coming into the pandemic, asset price growth was solid and running above inflationary levels. In recent years, top-tier assets in the market have been able to achieve pricing north of $400/SF.

While it is too early to tell where pricing heads, current conditions are unlikely to provide a tailwind for asset values in the coming quarters. Centrally located towers may experience significant pricing corrections as occupiers reevaluate space needs. CoStar’s baseline and downside scenarios all call for price declines and cap rate expansions for at least the near term, to varying extents.

Looking ahead, structural changes to office demand because of the pandemic could either increase or hinder office valuations. The high-density floorplans that have been favored by many tenants are currently being scrutinized. A shift to more space per employee could increase demand for office space, which would likely lift asset values. Some occupiers are considering a “hub-and-spoke” model where small satellite offices in the suburbs complement a diminished downtown presence to provide flexibility to employees. Conversely, the current work-from-home arrangements could lead office occupiers to rethink their office needs as firms may grant employees the flexibility to continue working from home, full or part-time. Some large tech firms have announced that employees may work from home indefinitely, while many large office occupiers remain committed to the traditional office, including most finance and real estate firms.

Economy

Though Miami has regained some jobs lost in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, the local economy continues to feel the impact of lockdowns and a high caseload. As of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) release of August jobs figures, the metro was still down about 90,000 jobs since March.

In March and April when the economy went into lockdown, Miami lost more than 160,000 jobs. Florida started to gradually re-open establishments in mid-May which led to a recovery of about 25,000 jobs in Miami that month. In June, 40,000 more jobs came back, reflecting a to a total recovery of 40% of the jobs lost. But by July, as the city continued to contend with the spread of the virus, distancing mandates and limits on indoor gatherings were again implemented and about 8,000 jobs were lost. About 16,000 jobs came back in August but by the BLS’s August release, Miami had recovered just 45% of the more than 160,000 jobs it had initially lost.

Miami has been doubly impacted by the pandemic in that the city was a hotspot for the virus and that its economy relies heavily on both domestic and international travel. Tourism has been greatly interrupted and the cruise industry with which Miami is intertwined will likely feel the lingering effects of the pandemic for some time. Prior to the job losses stemming from the pandemic, more than 150,000 people in Miami worked in the leisure and hospitality industry. About 70,000, nearly 50%, of those jobs were lost by the end of April.

Retail trade jobs have also been hit hard while shops have closed, and many people choose to stay home even after mandates have been lifted. About 145,000 people worked in retail trade in Miami pre-pandemic. As of the BLS’ August report, about 12,000 such jobs had been recovered since the state re-opened in mid-May, but the sector was still down more than 10,000 jobs from February.

The greater trade employment sector, excluding retail trade, has struggled as well. In addition to the more than 22,000 retail trade jobs lost in March and April, the market lost an additional 11,000 non-retail trade, transportation, and utilities jobs. By August, the sector was still down more than 8,000 jobs, having recovered just 25% of losses.

While the shape of the economic recovery from the pandemic is yet to be seen, in Miami it is likely to be prolonged. The market had to implement some of the longest lockdown periods due to the heightened spread of the virus, and the high cost of living is likely to continue driving net negative domestic migration from the city. Still, the market should benefit from its diversity. No one industry accounts for more than 15% of Miami’s jobs, helping to insulate the city from higher losses as a proportion of the workforce during downturns.

Miami-Dade County is also one of the 10 largest in the U.S. by population and continues to grow. Growth has slowed, recently led by a decline in international migration which has been off-setting net negative domestic migration in recent years. International migration could decline further because of the pandemic. But while population growth was some of the lowest in Florida in 2019, it slightly outpaced the National Index.