Summary

The recent Florida coronavirus case resurgence forced local authorities to put Miami’s phase one reopening process on pause to protect public health, but with that came prolonged economic uncertainty. The metro’s retail sector continues to suffer the brunt of the pandemic, as most retail businesses operate under significant capacity and opening hour limitations, while most entertainment venues remain completely shut.

The economy’s paused reopening, the reenactment of some social distancing measures, and the absence of visitors have translated into a heavy spending reduction in the metro. While unemployment benefits have provided support for grocery stores and other related essential businesses, it is unclear how adequate federal and local government small business support measures are for Miami’s many smaller businesses, which employ the majority of the metro’s retail workforce. Much of the small business assistance so far has come in the form of loans, which can translate into a substantial future financial burden, given the generally tighter margins smaller businesses operate under.

Vacancies look set to rise over the next few quarters, as a significant part of space could become available amid the ongoing the economic disruption. Supply is on the rise, as Miami has one of the country’s strongest construction pipelines relative to inventory. It is unclear what the retail rent collection picture looks like, but it is likely substantially worse than other commercial real estate sectors. Investment activity over 20Q2 dropped significantly when compared to 19Q2, but some deals closed. Investors were more recently active in suburban areas, while some of the metro’s higher-profile areas, such as Miami Beach, did see a couple of deals.

Leasing

The failure to contain the coronavirus pandemic is keeping visitors away and residents under strict social distancing measures. The use of a mask is mandatory across the county. Most retail outlets operate under severe restrictions, while all entertainment venues are closed.

Miami-Dade County’s phase one market opening process, which started in early May, was put on pause in late June, with several social distancing measures brought back. This put additional upward pressure on vacancies, both in Miami’s visitor-driven submarkets closer to the ocean as well as in the resident-driven areas, which account for most of the metro’s retail stock.

Support packages put in place by both the federal and local governments since March offer some relief for Miami’s smaller retail tenants. But given the drastic cuts in retail spending and the fact that most of the metro’s retail tenants are small businesses, it is unclear how adequate the support measures are in countering the loss of business since the pandemic’s onset.

Miami’s visitor-driven retail areas include Miami Beach, the Wynwood Arts District, Brickell City Center, Coral Gables’ Miracle Mile, and the Rodeo Drive-style Design District in Midtown. Visitor spending in these areas ground to a halt, as very few domestic and almost no international visitors have come to Miami over the past few months. While many large national brands are in these areas, a lot of the space is occupied by smaller business tenants, such as restaurants.

The most recently reported yearly numbers showed a record-breaking 16.5 million visitors over 2018, which provided an economic impact of nearly $18 billion on Miami’s economy, close to 5% of Miami’s Gross Metro Product. The spending is disproportionately impacted by international visitors, who contribute over half of the total expenditures. Almost all international flights have been canceled. The U.S. government has placed restrictions on visitors from many countries, including the European Union.

Some Miami resident traffic continued to flow to the traditionally visitor-driven areas, prompting local governments to impose more-stringent than county-wide social distancing measures. For example, Miami Beach’s Ocean Drive is under more strict curfew hours, relative to the rest of the county.

Spending in residential areas fares better, especially for grocery stores and other essential businesses. Restaurant and other entertainment venues continue to suffer the most. Restaurant dining across Miami-Dade County is only allowed outdoors; tables must be appropriately distanced; and gatherings, even on the street, are limited to 10 people.

The government support package has kept those out of a job spending, something that has likely prevented more drastic consumer spending cuts. However, Florida’s unemployment benefits last 12 weeks, relative to the 24-week national average. As we are more than three months from the onset of the pandemic, more unemployed must rely on the federal government stepping in to provide supplemental support.

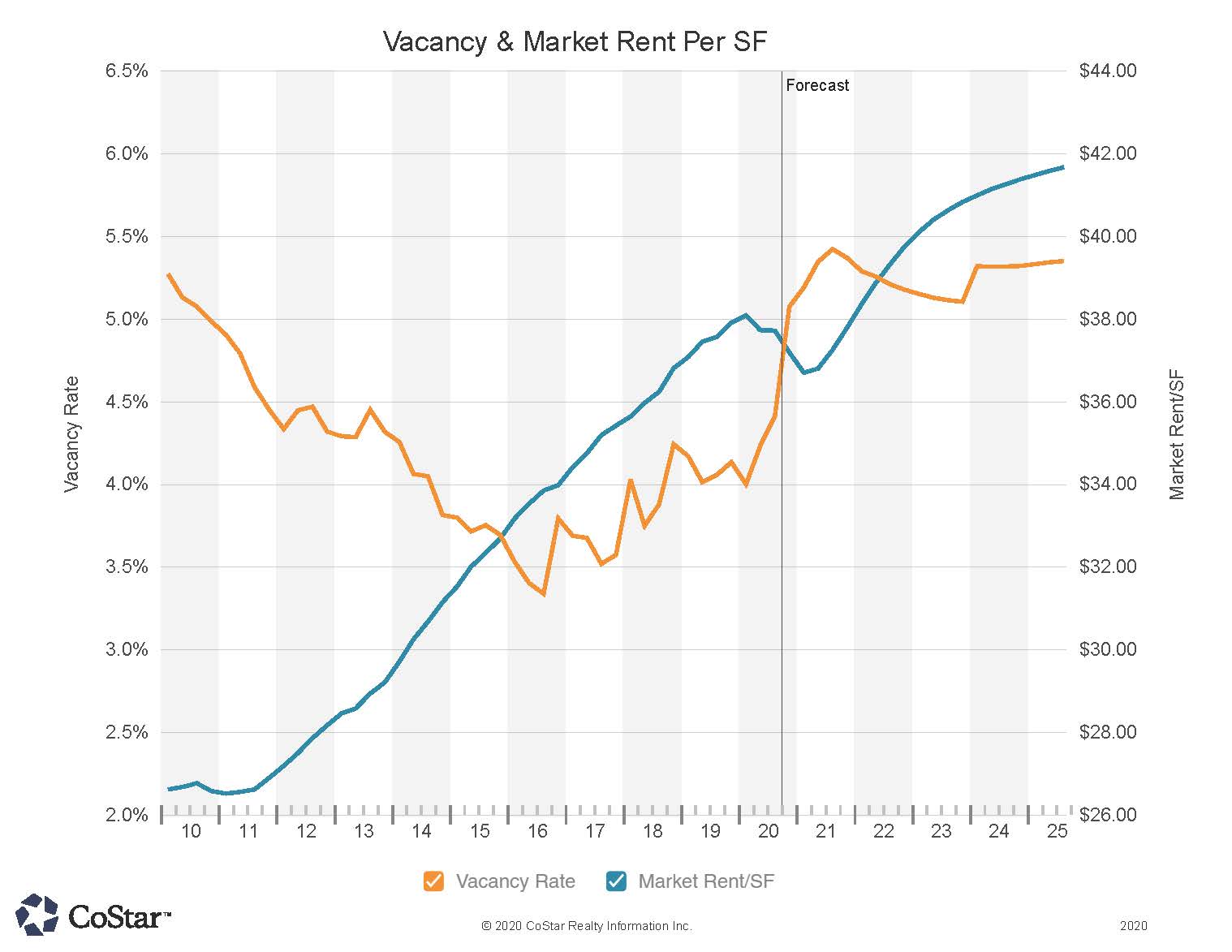

Considering a strong supply pipeline and amid a weakening economic outlook, the forecast calls for vacancies to rise over the next year.

Rent

Average rents in Miami are close to $38.00/SF, almost double the national average, but they vary significantly and depend on location spending drivers.

Submarkets that see more visitor spending, such as Miami Beach, Wynwood, and the Design District, maintain rents that well are above the metro average. In South Beach and the Design District, rents can easily exceed $100/SF, and many top national and international brands maintain a presence in these areas.

Urban submarkets, such as Brickell and Downtown Miami, see a fair share of visitor spending, but they are primarily driven by high-income residents, many of which live in these areas, and by office workers.

Brickell rents run over $60/SF. Close to half Brickell’s retail stock is part of the 2018-delivered Brickell City, where rents run above the $60/SF. Rents in the older Mary Brickell Village Shopping area and in other street-level retail typically run below $60/SF.

Some of the older retail buildings in Downtown Miami’s historic center register rents below the submarket’s average rent of $40/SF. Newer mixed-use developments, including Miami World Center and Miami Central, that host primarily experiential retail carry asking rents that are above the submarket average.

Suburban areas where spending is primarily driven by Miami residents, such as Miami Airport, South Dade, and Medley/Hialeah, register rents that are below the metro average and mostly range between $25/SF and $35/SF.

While retail demand remained healthy for the latter part of 2019, the sharp supply rise caused rent growth to decelerate significantly at the beginning of this year before the onset of the pandemic. Rent growth decelerated much faster, across the board, since March.

The demand outlook remains uncertain, as the number of Miami visitors declined substantially over the past few months. Residents also continue to spend less, as many retail businesses operate under severe restrictions. The absence of information on rent collection likely indicates that retail rent collection rates are substantially below that for other commercial real estate sectors.

On the back of the rising economic uncertainty and amid the recent coronavirus case surge, the forecast is calling for rents to continue declining over the next year.

Sales

Transaction volume over the year before the coronavirus pandemic’s onset declined significantly, when compared to the prior year. Many of the metro’s most expensive retail assets, located in tourist areas, changed hands earlier in the cycle. More recently, buyers became more opportunistic and went after shopping centers in growing multifamily and office suburban markets.

Private investors drove close to 80% of the past year’s deal volume. Users accounted for just under 20% of the year’s activity, while institutional investors accounted for less than 5%. Local investors drove close to 60% of activity, while national investors accounted for close to 35%. International investors drove less than 5% of the deal activity over the past year.

Rising economic uncertainty over the past few months has made lenders and investors more reserved, causing deal volume to drop further. The 20Q2 transaction volume was about a third of that in 19Q2. But despite the deal volume slowdown, several deals completed recently, mostly in Miami’s suburbs.

The current uncertain environment suggests that transaction activity is likely to remain subdued for several more quarters. On the back of rising economic uncertainty, the forecast calls for prices to decline over the next year.

Economy

Though Miami has regained some jobs lost in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, the local economy continues to feel the impact of lockdowns and a high caseload. As of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) release of August jobs figures, the metro was still down about 90,000 jobs since March.

In March and April when the economy went into lockdown, Miami lost more than 160,000 jobs. Florida started to gradually re-open establishments in mid-May which led to a recovery of about 25,000 jobs in Miami that month. In June, 40,000 more jobs came back, reflecting a to a total recovery of 40% of the jobs lost. But by July, as the city continued to contend with the spread of the virus, distancing mandates and limits on indoor gatherings were again implemented and about 8,000 jobs were lost. About 16,000 jobs came back in August but by the BLS’s August release, Miami had recovered just 45% of the more than 160,000 jobs it had initially lost.

Miami has been doubly impacted by the pandemic in that the city was a hotspot for the virus and that its economy relies heavily on both domestic and international travel. Tourism has been greatly interrupted and the cruise industry with which Miami is intertwined will likely feel the lingering effects of the pandemic for some time. Prior to the job losses stemming from the pandemic, more than 150,000 people in Miami worked in the leisure and hospitality industry. About 70,000, nearly 50%, of those jobs were lost by the end of April.

Retail trade jobs have also been hit hard while shops have closed, and many people choose to stay home even after mandates have been lifted. About 145,000 people worked in retail trade in Miami pre-pandemic. As of the BLS’ August report, about 12,000 such jobs had been recovered since the state re-opened in mid-May, but the sector was still down more than 10,000 jobs from February.

The greater trade employment sector, excluding retail trade, has struggled as well. In addition to the more than 22,000 retail trade jobs lost in March and April, the market lost an additional 11,000 non-retail trade, transportation, and utilities jobs. By August, the sector was still down more than 8,000 jobs, having recovered just 25% of losses.

While the shape of the economic recovery from the pandemic is yet to be seen, in Miami it is likely to be prolonged. The market had to implement some of the longest lockdown periods due to the heightened spread of the virus, and the high cost of living is likely to continue driving net negative domestic migration from the city. Still, the market should benefit from its diversity. No one industry accounts for more than 15% of Miami’s jobs, helping to insulate the city from higher losses as a proportion of the workforce during downturns.

Miami-Dade County is also one of the 10 largest in the U.S. by population and continues to grow. Growth has slowed, recently led by a decline in international migration which has been off-setting net negative domestic migration in recent years. International migration could decline further because of the pandemic. But while population growth was some of the lowest in Florida in 2019, it slightly outpaced the National Index.