If the central bank ever steps away from backstopping mortgage bonds, the consequences could be dire.

(Bloomberg Opinion)—When the definitive story is written about U.S. financial markets during the coronavirus pandemic of 2020, expect America’s housing market to play a starring role.

In many ways, it’s hard to reconcile worsening Covid-19 outbreaks with record-high levels for the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 Index, or the unprecedented surge in unemployment earlier this year with the fact that American households are by some measures in their best financial shape overall in decades, regardless of wealth level. It becomes a bit easier to see what’s happening when using the mortgage market as a frame of reference.

Benchmark 30-year mortgage rates have slowly but surely dropped to record lows throughout the pandemic, touching 2.78% earlier this month, according to Freddie Mac data. This has naturally encouraged more and more homeowners to refinance their mortgages, thereby allowing them to lower their monthly payments or tap equity. With more cash in their pockets, these people have kept spending levels relatively steady while also socking money away or investing in stocks or other assets. Janet Yellen, the former Federal Reserve chair and contender to be President-elect Joe Biden’s Treasury secretary, said during the Bloomberg New Economy Forum on Monday that a “savings glut” was helping to prop up financial markets.

What she didn’t say, and what’s flown largely under the radar amid the central bank’s efforts to bolster the economy, is the Fed’s role in pushing the $6.8 trillion mortgage-backed securities market to extremes. I wrote last month that the Fed might resort to infinite quantitative easing to support the $20.4 trillion U.S. Treasury market. But if the central bank ever steps away from backstopping mortgage bonds, there’s reason to believe the consequences could be even more dire.

As it stands, the Fed has bought more than $1 trillion of mortgage bonds since March, a record pace, and now holds $2 trillion of the securities on its balance sheet. That easily eclipses the previous high during the last economic recovery. Central bankers have pledged repeatedly to keep adding bonds each month “at least at the current pace,” which is often quoted as $40 billion. But that’s actually a net figure: Total monthly purchases tend to be closer to $100 billion because borrowers’ principal repayments take out some debt already on the Fed’s balance sheet.

Buying Spree

In recent weeks, the Fed has taken its mortgage-bond buying even further. On Oct. 29, it took the unprecedented step of purchasing conventional 30-year securities with a 1.5% coupon, the lowest now available. Though it’s been careful not to go overboard, the move is nonetheless a clear indication that the central bank doesn’t expect to raise interest rates in the years to come.

All of this serves to squeeze mortgage-bond investors in higher-rate securities. Most of them bought the debt at a premium, and the constant reduction in lending rates leaves them vulnerable to prepayment risk as homeowners refinance and pay off their existing obligations at par. But it would be arguably even more painful if investors are herded into ultra-low coupon MBS, only to see rates rise. Known as “extension risk,” fund managers left holding 1.5% or 2% MBS could be saddled with huge losses if longer-term interest rates start to increase next year as the U.S. economy rebounds and inflation starts to pick up on the back of a Covid-19 vaccine.

It should be clear by now that the Fed is in a tricky spot. On the one hand, pushing down long-term mortgage rates is one of the most direct ways the central bank can bolster household balance sheets. And yet the Fed desperately wants inflation above 2% and for the U.S. economy to bounce back. If America indeed comes roaring back next year, longer-term Treasury yields should jump higher, as would the benchmark 30-year mortgage rate. But if that happens too quickly, and homeowners can no longer free up cash, that removes a key pillar of support for the economic recovery.

Main Street Paradise

JPMorgan Chase & Co. may have a temporary answer for the Fed’s dilemma. Michael Feroli, the bank’s chief U.S. economist, predicted on Monday that the Fed will announce at its December meeting that it will tilt its bond buying toward longer-dated Treasuries, potentially doubling the weighted average maturity of its $80 billion of purchases. This would presumably pin down 10-year and 30-year yields, and, by extension, mortgage rates, even with the economy on the mend. Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida on Monday indicated that policy makers are still monitoring asset purchases, though he gave no indication they were leaning in the direction of extending maturities. Still, it’s the logical next step, in the same vein as Operation Twist.

Regardless of whether policy makers go that route, it’s hard to see a way out of the mortgage market for the Fed without causing at least a hiccup in the U.S. housing market and an implosion at worst. As my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Aaron Brown wrote last week, even though U.S. home prices are nearing all-time highs, the current market isn’t necessarily a disaster in the making because the high valuations are the result of rock-bottom interest rates. However, as he made clear: “It’s one thing to be a peak valuation, it’s another to be at peak valuation with no discernible upside.”

If there’s a modest correction in housing prices, that shouldn’t be too disruptive for the economy as a whole. Rather, it’s the second-order effects of higher mortgage rates that should concern investors. As Bloomberg News’s Christopher Maloney reported, aggregate Fannie Mae 30-year prepayment speeds in September increased to their fastest since April 2004, and Wall Street analysts expect that the current “perfect refinance environment” can last awhile longer. If that doesn’t happen, for whatever reason, it would remove a crucial variable behind sustained consumer spending and the rally across risky assets.

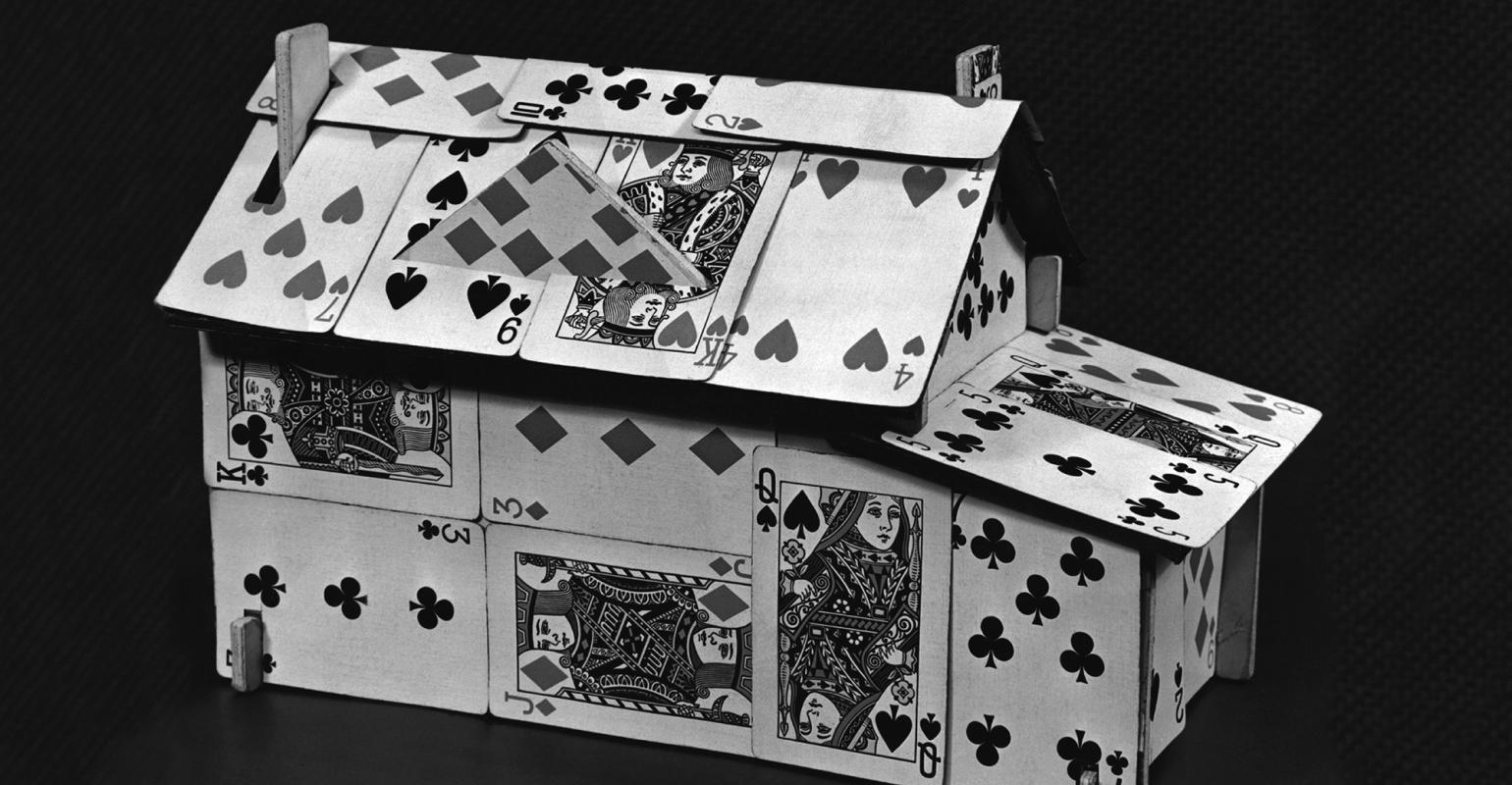

As the calendar turns to 2021, Fed officials will need to figure out how to engineer a soft landing for the housing market. The refinancing boom the central bank engineered has helped countless Americans get through the pandemic. But it can’t afford to see it go bust. Most likely, the Fed won’t be able to extricate itself from buying mortgage bonds for at least the next several years, and possibly longer, or else risk toppling the entire house of cards it built.