Summary

Miami is South Florida’s largest and most tenant-diverse industrial market. Demand is primarily driven by the local economy and by trade flow through Miami International Airport (MIA) and Port Miami. Some of the metro’s more substantial submarkets are in the center of Miami-Dade County, adjacent to major high arteries, around MIA.

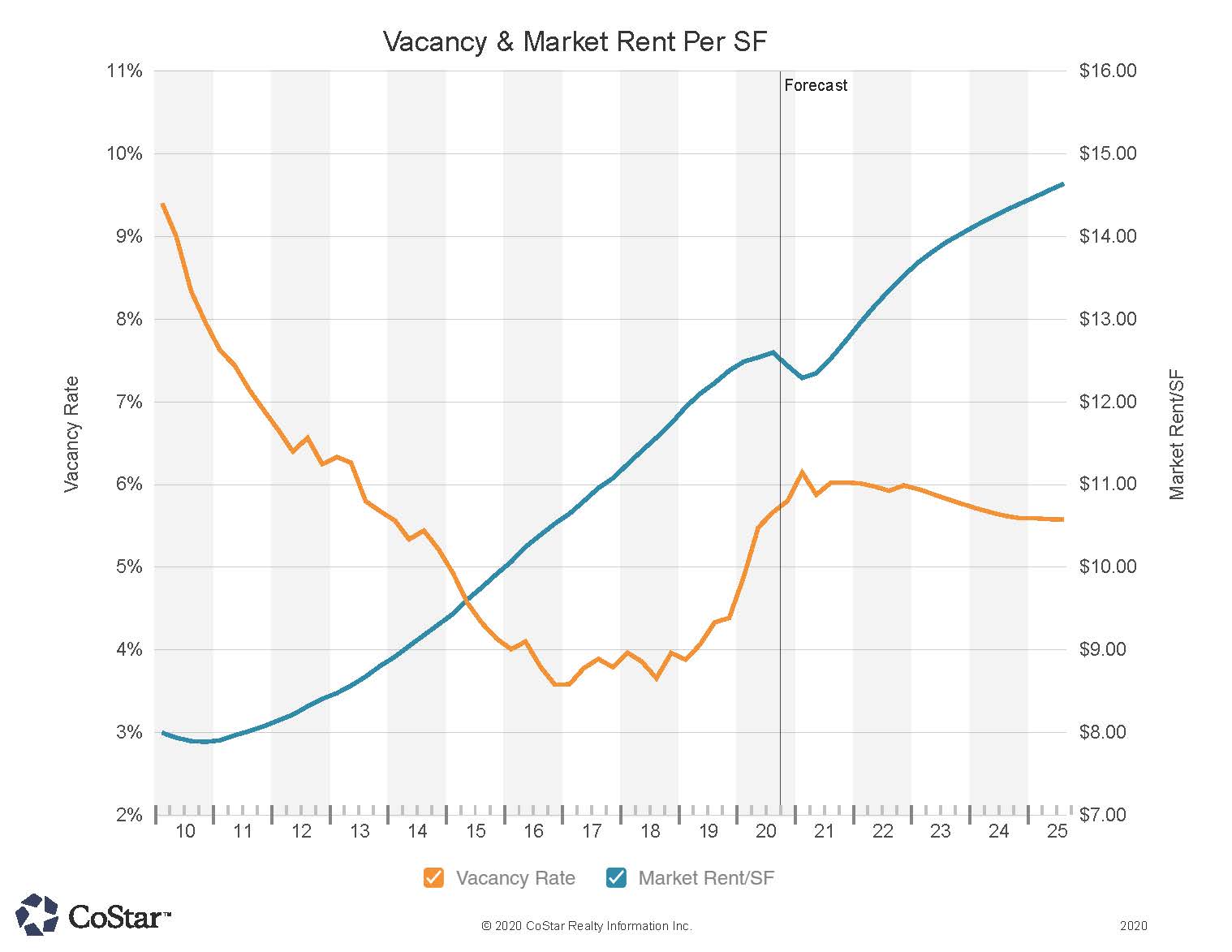

Miami’s industrial sector performed well, with vacancies remaining below the national average and reaching a plateau of around 4% for the better part of the past five years before the coronavirus pandemic onset. In addition to a growing Miami economy for over a decade, e-commerce provided an industrial demand boost, as many of the country’s large e-tailers extended their footprints, both to service the local market and as a base for their Latin America operations. The recent expansion of the Panama Canal is also a positive development for this market’s longer-term prospects. The expansion has made it possible for much larger vessels to go through the canal, and Port Miami is expected to benefit, as the Asia trade route has become more efficient. Port Miami is the closest seaport to the Panama Canal, but it might take several years for major trade routes to be redrawn.

Vacancies have recently drifted slightly higher, as supply has risen, and leasing volume has declined. Market uncertainty has pushed decision makers into a holding pattern, making many tenants more hesitant to a sign substantial leases well ahead of expiration. As a result, 20Q2 deal activity was primarily driven by renewing expiring leases, though several substantial new leases were signed in the second quarter of the year, with Amazon leading the way.

The most pronounced supply trend over the past couple of years is the shift of construction away from Miami Airport West, the metro’s largest submarket, and other airport-adjacent areas. A developable land shortage, together with the desire of many trade and logistics tenants to be as close as possible to MIA, has driven prices up in the submarket around the airport and made it inaccessible for many prospective tenants. North Miami Beach, Outlying Miami-Dade, and Medley are the submarkets that have benefited from the construction shift, especially on the west side closer to the Everglades. That is where most of the current development activity is happening.

The level of construction slowed down in March, as many projects that were set to break ground remained under a proposed status. As a result, supply adjusted, and while the overall space under construction is a little below the national average, much of the under-construction space is being developed by owner/users. The prelease rate is close to 70%.

While industrial continues to be the most coronavirus-insulated sector, it is likely to experience some negative demand impact from the pandemic’s economic fallout. The severity of the impact will depend on how long it will take the region’s economy to recover, as well as when international trade will resume. On the back of rising economic uncertainty, the forecast calls for vacancies to rise mildly and prices to fall for the first time in over a decade.

Leasing

Miami’s vacancy rate remained stable throughout the year before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, as demand trailed deliveries. But the coronavirus-driven market disruption and the economic uncertainty that ensued have slowed down deal making, while deliveries continued, and that has put upward pressure on vacancies.

Miami industrial demand is primarily driven by local economic growth and trade going through Miami International Airport, which is one of the country’s largest international freight airports and accounts for 70% of Miami’s trade activity. Port Miami accounts for the rest. Trade activity continues to fuel Miami industrial demand, but dollar trade volume declined over the past few years. Trade flow has been severely disrupted by the pandemic.

International trade growth has declined in recent quarters, but the rise of e-commerce has countered the trade-driven demand loss. Some of the country’s largest e-retailers are capitalizing on Miami’s extensive international connections, headquartering their global e-commerce distribution operations in the area, especially those covering Latin America.

Leasing activity declined by close to 15% in 20Q2. At close to 45%, the decline is much more pronounced when comparing 20Q2 leasing with 19Q2 leasing activity. The decline in leasing activity reflects many decision makers going on a holding pattern when it came to committing to large leases ahead of time, rather than weakening fundamentals.

E-commerce is a driver that will likely continue to make positive contributions towards Miami’s industrial demand growth, offsetting some of the losses from the more traditional international trade flow. The quarantine has boosted e-trade as more people went online for their shopping needs, but many e-tailers are also using Miami as a distribution base for Latin America.

On the back of rising economic uncertainty, the forecast is calling for vacancies to rise mildly over the next year but to remain below the national average.

Rent

Both Miami and national industrial 12-month rent growth decelerated over the past couple of years, after a decade of economic expansion. The Miami metro’s year-over-year rent growth remains close to the national average.

High-construction areas that are seeing new high-quality space come to market, such as Outlying Miami-Dade, North Miami Beach, and Medley, are registering average rent growth that is above the metro average. Miami Airport West and other popular submarkets that register low construction activity, are seeing rent growth that is close to the metro average. Smaller submarkets that are seeing no construction are seeing rent growth that is below the metro average. Unlike other Miami commercial real estate industry sectors, industrial continues to see rents rising, and while rent growth is lower than it was a year ago, it remains reasonably high.

On the back of the weakening economic outlook, that could potentially translate into lower industrial space demand, and amid slowing construction, the forecast calls for rent growth to slow further by the end of the year.

Sales

The current uncertain environment suggests that transaction activity is likely to slow as uncertainty weighs more heavily on investors and lenders. Investors will need to reassess their projections for future cash flows and property performance, as the coronavirus-spawned recession renders their projections increasingly uncertain. Lenders are also more reluctant to lend as the recession progresses, instead taking a pause to evaluate rent growth assumptions and deal profiles. Meaningful declines in the deal volume are expected as a result, but first-quarter investment volume is tracking ahead of the activity registered at similar points within the quarter in prior years

As with the rest of the country, the coronavirus pandemic has disrupted financing and added uncertainty when pricing transactions that are currently in the pipeline. Lending spreads have recently widened significantly, something that could cause many deals that are now in the works to get canceled or renegotiated. As cash flows become less certain, valuations will become inherently riskier and, together with more expensive financing, will likely lead to a significant reduction in investment activity over the next few quarters as investors sit on the sidelines while the dust settles.

Economy

Though Miami has regained some jobs lost in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, the local economy continues to feel the impact of lockdowns and a high caseload. As of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) release of August jobs figures, the metro was still down about 90,000 jobs since March.

In March and April when the economy went into lockdown, Miami lost more than 160,000 jobs. Florida started to gradually re-open establishments in mid-May which led to a recovery of about 25,000 jobs in Miami that month. In June, 40,000 more jobs came back, reflecting a to a total recovery of 40% of the jobs lost. But by July, as the city continued to contend with the spread of the virus, distancing mandates and limits on indoor gatherings were again implemented and about 8,000 jobs were lost. About 16,000 jobs came back in August but by the BLS’s August release, Miami had recovered just 45% of the more than 160,000 jobs it had initially lost.

Miami has been doubly impacted by the pandemic in that the city was a hotspot for the virus and that its economy relies heavily on both domestic and international travel. Tourism has been greatly interrupted and the cruise industry with which Miami is intertwined will likely feel the lingering effects of the pandemic for some time. Prior to the job losses stemming from the pandemic, more than 150,000 people in Miami worked in the leisure and hospitality industry. About 70,000, nearly 50%, of those jobs were lost by the end of April.

Retail trade jobs have also been hit hard while shops have closed, and many people choose to stay home even after mandates have been lifted. About 145,000 people worked in retail trade in Miami pre-pandemic. As of the BLS’ August report, about 12,000 such jobs had been recovered since the state re-opened in mid-May, but the sector was still down more than 10,000 jobs from February.

The greater trade employment sector, excluding retail trade, has struggled as well. In addition to the more than 22,000 retail trade jobs lost in March and April, the market lost an additional 11,000 non-retail trade, transportation, and utilities jobs. By August, the sector was still down more than 8,000 jobs, having recovered just 25% of losses.

While the shape of the economic recovery from the pandemic is yet to be seen, in Miami it is likely to be prolonged. The market had to implement some of the longest lockdown periods due to the heightened spread of the virus, and the high cost of living is likely to continue driving net negative domestic migration from the city. Still, the market should benefit from its diversity. No one industry accounts for more than 15% of Miami’s jobs, helping to insulate the city from higher losses as a proportion of the workforce during downturns.

Miami-Dade County is also one of the 10 largest in the U.S. by population and continues to grow. Growth has slowed, recently led by a decline in international migration which has been off-setting net negative domestic migration in recent years. International migration could decline further because of the pandemic. But while population growth was some of the lowest in Florida in 2019, it slightly outpaced the National Index.